FizzBuzz in FORTRAN 1

Fortran is the first high-level programming language. Its latest iteration, Fortran 2023 is a modern language by today’s standards. However, its very first version, released in 1956, is rather simple, containing only a small set of commands.

To get a feel for what it was like, I'll walk through a FizzBuzz implementation in this post. Let's start with the code:

c FizzBuzz program in FORTRAN 1

1 FORMAT (I6)

READ 1, N

DO 100 I=1,N

IF (XMODF(I,15)) 100,10,20

2 FORMAT (8Hfizzbuzz)

10 PRINT 2

GO TO 100

20 IF (XMODF(I,3)) 100,30,40

3 FORMAT (4Hfizz)

30 PRINT 3

GO TO 100

40 IF (XMODF(I,5)) 100,50,60

4 FORMAT (4Hbuzz)

50 PRINT 4

GO TO 100

60 PRINT 1, I

100 CONTINUEThe layout

The first thing to notice is the strict layout of the program. Comments are marked by a c at the start of the line. The actual code always starts at the 7th column.

This is not just formatting convention, it is enforced by the language:

- A

cin the first column marks a comment. - Columns 1-5 are numeric labels.

- Column 6 is used for continuing the previous line (does not occur in this code sample).

- Columns 7-72 contain the actual code.

The line length can not be more than 72 characters.

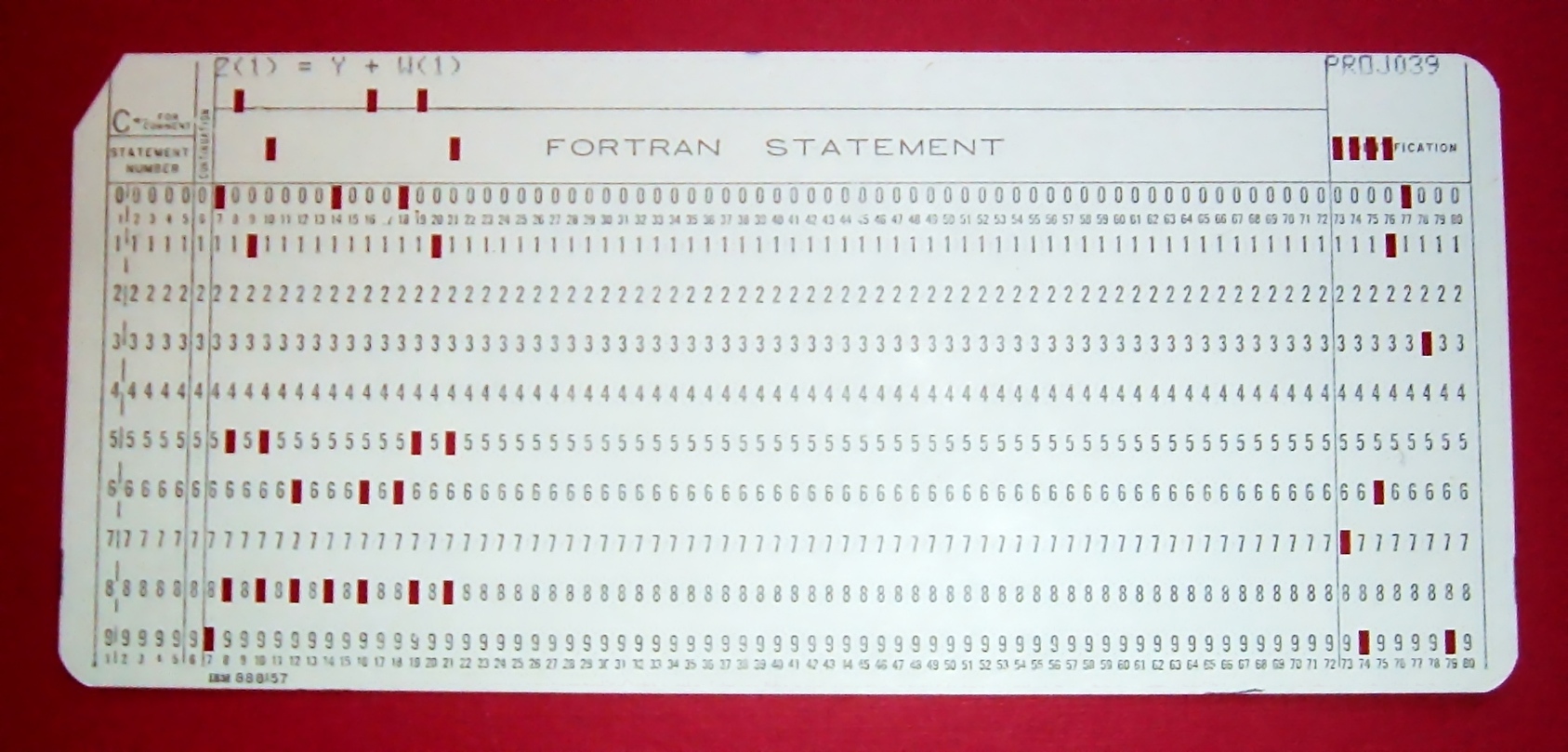

Why is this strict structure? Originally, the code was written on a punch card, and the physical layout of the card dictated the position of the parts of the statement. A typical punch-card at the time looked like this:

Notice how the comment and continuation fields are marked on the card.

I/O

Let's dive into the I/O first. Each I/O operation consists of two lines. The first is the format statement, the second is the actual command:

1 FORMAT (I6)

PRINT 1, IThis prints the value of I, using the format labeled 1. The format string I6 means an integer, using up to 6 digits. Labels can be any numbers.

Another unusal aspect is how strings are handled:

4 FORMAT (4Hbuzz)

PRINT 4Instead of using " or ', Fortran denotes strings in a special way: 4Hbuzz. 4 indicates the length of the string, and H (standing for Hollerith-string) tells the compiler that the following characters form a string. First, one would write the length of the string, then the separator character H, and finally the string itself.

Control sequences

Fortran only had two control structures: three-way IFs and DO-loops.

Three-way IFs

First, let's explore three-way IFs:

IF (XMODF(I,15)) 100,10,20The expression inside the parentheses must evaluate to a number (in this case the remainder of I mod 15). Execution then jumps to one of the three labels depending on whether the value is negative, zero, or positive, respectively. In this example, if I is divisible by 15, the program jumps to line 10.

There are no endif or else blocks. There aren't even boolean conditionals, only a comparison based on a numeric value. Logical comparisons can be simulated with a three-way IF. For example, to test if a variable is equal to 5:

IF (N-5) 20,10,20

10 EQUALS=1

GO TO 30

20 EQUALS=0

30 ... This works by subtracting 5 and checking whether the result is zero. Of course, subtracting numbers can lead to underflow errors, so this was something you had to pay attention to.

In practice, IF behaves more like a conditional jump rather than the structured conditional expressions we are used to in modern languages.

DO loops

The other control structure is the DO loop:

DO 100 I=1,N

...

100 CONTINUEThis iterates the variable I from the starting value (here 1) until the ending value (N). The number following DO is the label of the corresponding CONTINUE statement. Despite its name, CONTINUE does not behave like the continue keyword in today's languages. Instead, it simply marks the end of the loop body and causes execution to jump back to the top of the loop.

The lack of a statement block suggests that you could go crazy and write interleaved loops:

DO 100 I=1,N

DO 200 J=1,N

...

100 CONTINUE

...

200 CONTINUEHowever, this was not allowed by the compiler The DO/CONTINUE pairing imposes a structured block, making it more than mere syntactic sugar for a GO TO. This is an early hint of block structure in programming languages.

Similarly to IFs, there are no conditional loops. Any looping logic beyond simple iteration had to be built using IF statements and GO TOs.

What is missing?

As the first high-level language, Fortran 1 lacked many features that later became standard. There are no functions or subroutines, no boolean type, and no structured control blocks. Since there are no functions, all variables are effectively global.

Although some of these concepts were already invented at the time, they were not part of the language. For example,the idea of functions (or subroutines as they were called back then) came up around 1946 but is missing from the language.

As a summary, FORTRAN, short for Formula Translator, lives up to its name. It allows mathematical expressions to be written in a natural, readable form, which was revolutionary at the time. However, control flow is still built from jumps, logical operations must be assembled from numeric tests, and there is no way to encapsulate or reuse code. In that sense, FORTRAN still feels like a higher-level assembly language.

Legacy

Interestingly, many of these structures survived for a very long time. Hollerith strings were removed in 1997, while three-way IFs only in 2018! Notably, the column-based layout (code starting in column 7) is still recognized, though it is deprecated and no longer required.